In 1982, the residents of Warren County, N.C., gathered to protest the state’s decision to dump thousands of pounds of soil contaminated with PCB oil in the predominantly black and low-income county.

This series features portraits of community members and/or places that are currently active in raising awareness for the events that occurred in Warren County which sparked the Environmental Justice Movement. The portraits are presented as diptychs alongside photos of the community members that were taken around the time they first became involved with the protests forty years ago.

“We lost the battle, but won the war.”

Before the aboliton of slavery, Warren County was at one point the most affluent county in North Carolina. Many freed slaves of Warren County and surrounding areas remained in the region, as there was nowhere else for them to go. Warren County thus became a predominantly black community, and in turn has since been neglected politically, socially, and economically. It is no coincidence then that the state of North Carolina deemed Warren County as the perfect location for a landfill chock-full of toxic waste in 1982. As one walks around downtown Warrenton, they might notice that infrastructure remains in an eery state of limbo, aching to be revitalized. Forty years after the 1982 protests, community members are now hoping to transform a devastating loss into educational resources by creating more sustainable spaces.

Top image courtesy of Harriet B. Cooper and the Warren County Memorial Library.

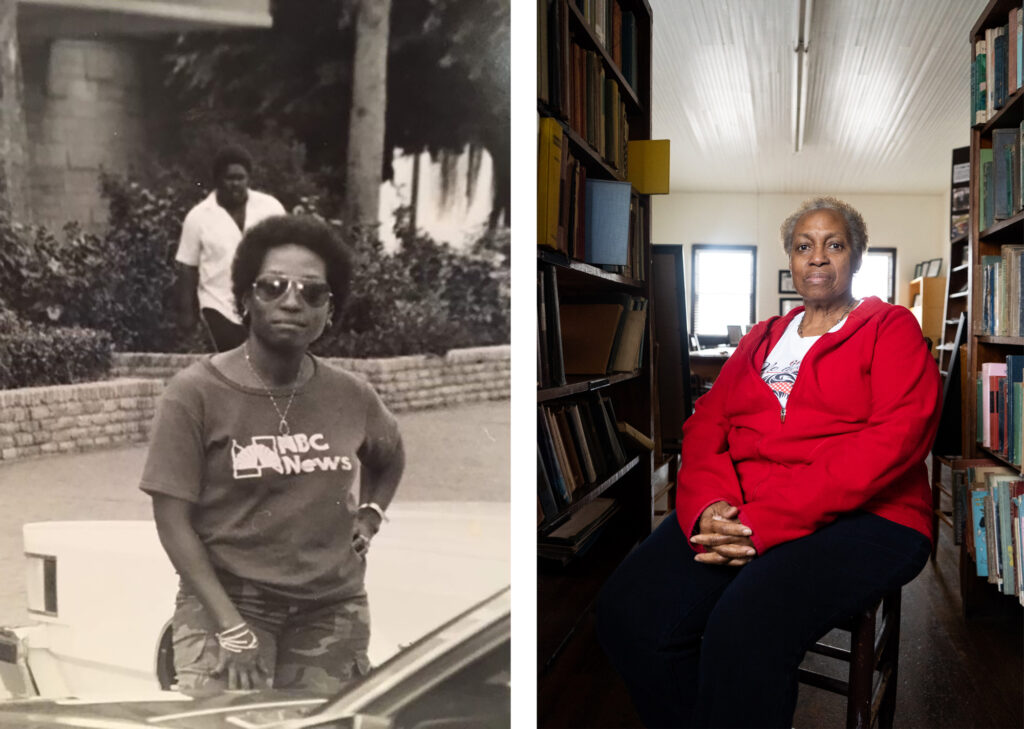

Shauna Williams

Shauna Williams, President of the Warren County Community Center, sits for a portrait in the Community Center on Feb. 4, 2022.

Williams is a retired NBC broadcast journalist who has reported on everything from the death of Princess Diana to the Challenger explosion. One of her earlier experiences with breaking news was in 1978 when she covered the illegal dumping of PCB oil in several North Carolina counties for the Duke University radio station.

“The part that really drives me crazy is that they had options. They had much better options. And still, they chose to put it all here, in Warren County. It blows my mind,” Williams said. Years later, Williams returned to Warren County as a resident after meeting her husband, a Warren County native. “We lost the battle, but we won birthing a movement, so in the end we are winners.”

Photo on left courtesy of Shauna Williams.

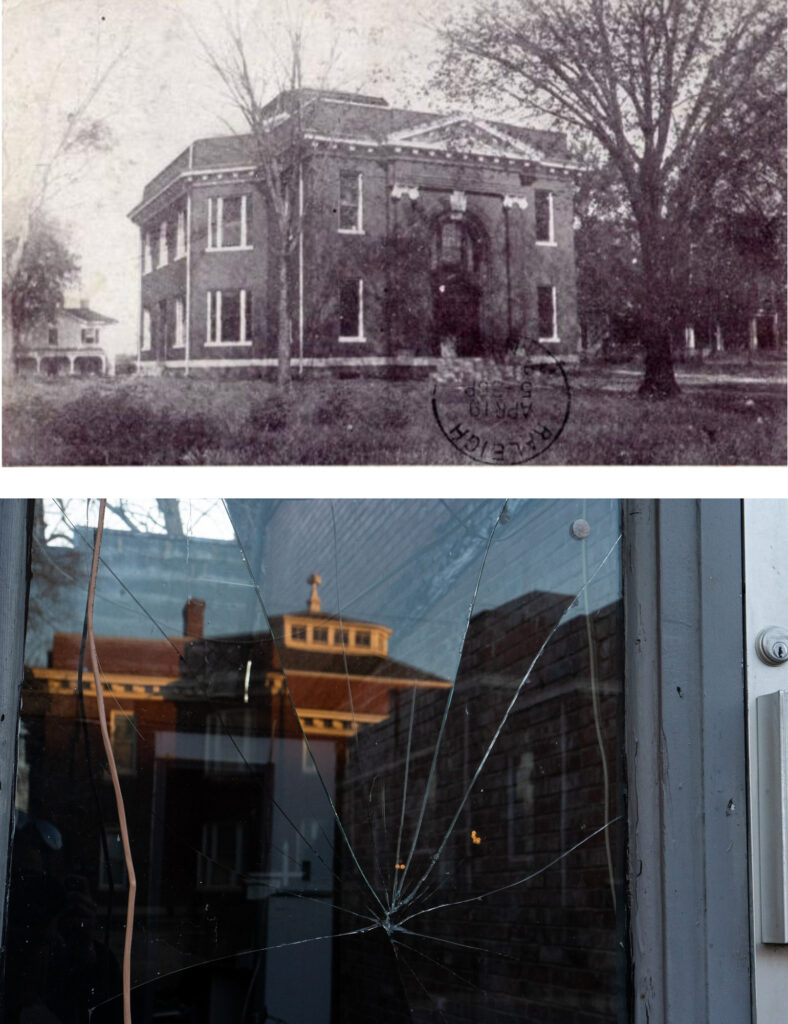

Warrenton Courthouse

The Warren County Courthouse, built in 1906, is located at 109 S Main St. in Warrenton, N.C. The historic building was where activists were tried for protesting the state’s dumping of soil contaminated with PCB oil.

The courthouse continues to retain its position as a center for political and social change. Following the 2017 riots in Charlottesville, V.A., a confederate statue was removed to prevent potential confrontation, violence, and protest.

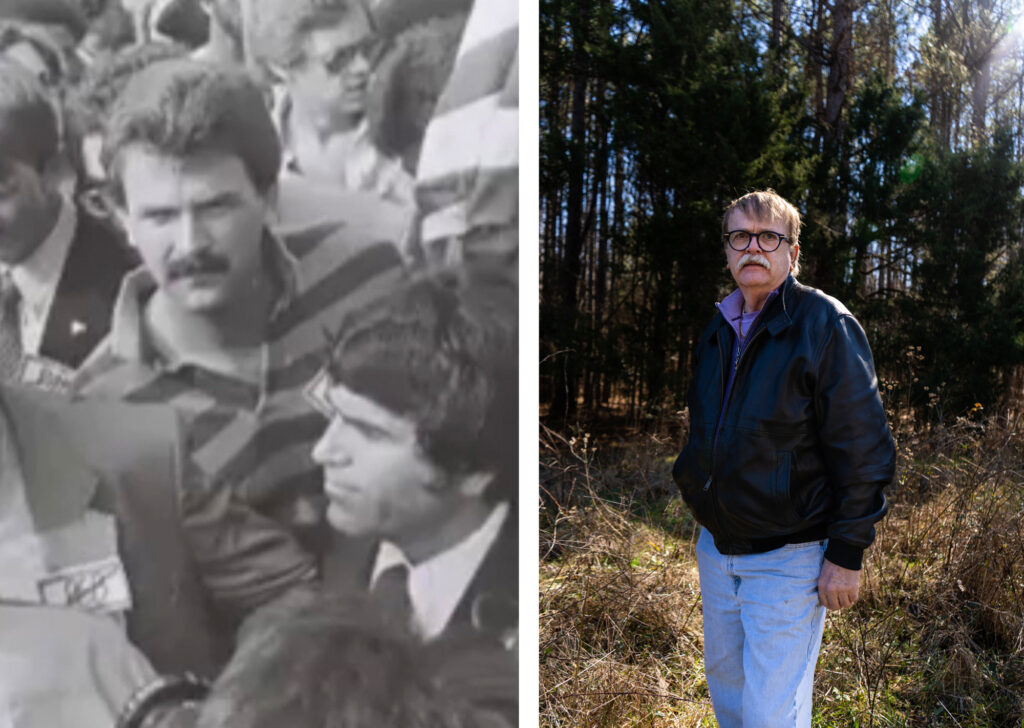

Wayne Moseley

Wayne Moseley, a Warren County native, poses for a portrait just feet away from the notorious landfill where the state of North Carolina discarded 40,000 cubic yards of contaminated soil.

Moseley remembers being one of the first protesters arrested and taken to jail. “The Highway Patrol began arresting and leading us to the waiting prison buses which had been parked in the hot sunshine,” Moseley recalls. “The windows were still up in the prison bus I was placed in. I thought I was going to bake like a chicken casserole!”

Moseley has since taken on and retired from the role of Dean of International Education at Living Arts College in Raleigh, and continues to use his platform to elevate stories of the events that sparked a movement forty years ago. “During the fall of 1982, the citizens of Warren County came together, found new friends among our neighbors, and forever left our mark on history,” Moseley says.

The photo on the left, courtesy of Wayne Moseley, depicts Moseley at the protest before his arrest.

Terry Jones

Terry Jones poses for a portrait in front of the Warren County Community Center on Feb. 12, 2022.

Jones was in high school when she participated in the 1982 protests against the dumping of soil contaminated with cancer-causing chemicals in Warren County. Jones is now the Executive Director of the Living and Learning Youth Center in Warrenton. She is in the process of developing a new program that will educate youth in Warren County about the 1982 protests and the importance of the environment. “We want them to know that if something bad happens to them or to their community that they don’t like, they have the option to speak up and protest it,” Jones says.

Photo on left courtesy of Terry Jones.

Rev. Bill Kearney

Community leader Rev. Bill Kearney sits for a portrait on the steps of Coley Springs Baptist Church in Warren County, N.C. on Feb. 18, 2022.

Kearney works with the Warren County African American History Collective, which engages members of the Warren County community with each other and with the world. Kearney says that most people who live in Warren County do not recognize the gravity of their role in starting the Environmental Justice Movement. He feels that his calling is to help them tell their stories and come to this realization. Kearney also hopes to transform Warren County into an educational center for learning about the history of environmental justice.

Photo on left courtesy of Rev. Bill Kearney.

Main Street

Despite every hardship that has struck Warren County, residents perservere by maintaining a strong community bond.

The photo on the left is a clipping from The Warren Record, taken on Feb. 29, 1984 by a staff photographer (unknown). The image shows the aftermath of a storm that ripped off the roof of a Main Street building.

Angella Dunston

On Feb. 25, 2022, Angella Dunston stands for a portrait in the very road she walked forty years ago when she protested the state of N.C.’s dumping of contaminated soil.

For six weeks in 1982, hundreds of protesters marched the roads of Warren County, and laid in the middle of the road to block trucks carrying the cancer-causing waste. “It was both a spiritual and scary experience,” says Dunston. “The community came together, and it was beautiful, but it was over something that we knew would seriously harm us.”

Dunston now uses her past experience with environmental justice to help other low-income communities that are facing similar hardships. She is currently the Director of Community Engagement and Advocacy for the N.C. Community Action Association.

Photo on left courtesy of Angella Dunston.